Recently, demonstrations supporting Palestine at an Ivy League university in New York have spread like wildfire to campuses across the United States. Watching as students occupy campuses and clash with law enforcement has left Jane Chin, a parent of a college student, feeling increasingly anxious. So, she asked The Human Calling Author Dao Feng He for guidance: I can't help but wonder, are the minds of this generation of young people so easily manipulated? What's most frightening is the discovery that a large portion of those occupying and vandalizing Hamilton Hall are not even students of the school, but rather members of the general public. I sought out Brother He and discussed my confusion about this event. Brother He pointed out that there are problems with America's immigration policy. A large number of illegal immigrants enter the country. Among them are individuals with different political intentions and special missions who slip through the cracks, gather within the United States, and form organized political movements or even rioting elements. This event may prompt many Jewish people to rethink what they have gained from donating funds to these elite schools. Many donations have gone to left-wing causes, supporting a large number of illegal immigrants, and a significant amount of funds have also helped many far-left and anti-divine policy agendas. This campus student movement provides a good opportunity to examine how Jewish funds have become a breeding ground for anti-Semitic sentiments, allowing elite universities to prioritize the admission of these students under unfair admission standards. Among these individuals, some have been trained with different political missions and infiltrate universities to organize protest activities, while other students, under the long-term leftist educational mindset of society, are extremely susceptible to manipulation. That's how this student protest movement so quickly expanded. All these problems can be traced back to the departure from divine principles. If money is used to support things that are against the will of God for political or other purposes, the ultimate impact is not only on society but also on one's own ethnicity and the entire country. In the book The Human Calling, Brother He categorizes morality as "human duty", and society uses moral laws to influence and regulate what people should do. In the case of this university student support for Palestine against Israel, however, it is manipulated by those with ulterior motives using a seemingly ambiguous moral perspective to manipulate innocent students. In contrast, God's grace and God's calling achieve "human calling." Moral law exists in every culture in the world, but only God's grace enables people to follow the will of God from within. I left the conversation with a grateful heart, yet also worried about this young generation that only knows human duty but not human calling.

Like so many Christians, Jane Chin questioned how to approach immigration issues. She wanted to know how best to love her neighbor while still remaining true to God's purpose and standards. So, she asked The Human Calling Author Dao Feng He for guidance: As an immigrant, I take immense pride in identifying myself as an American. The United States, at its core, is a nation forged by immigrants—some tracing their lineage back for generations, others having arrived just days ago. The issue of a significant number of illegal immigrants crossing the border remains a contentious topic, and in the face of this controversy, I find myself deeply empathetic. Many illegal immigrants endure prolonged separation from their families, including young children, as they pursue a better life. I lead a significantly more stable existence than they do; the critical distinction lies in the fact that I am a legal immigrant, whereas they are not. During a conversation with Brother He, I discussed my empathy towards illegal immigrants, delving into themes of Christian love and concern for the impoverished. He cautioned me not to overlook Christ's righteousness while discussing His love. Allowing illegal immigration is tantamount to opening America's borders to invasion—a lesson echoed in history, where even the mighty Roman Empire succumbed to foreign incursions. Humanity's endeavors to reach the heavens with the Tower of Babel resulted in the diversification of languages and the formation of distinct ethnic nations. Each individual should prioritize personal responsibility, followed by familial responsibility, and then national responsibility. Stripping away the family unit leads to a collective society akin to a communist commune. Destroying the nation erases its borders, thus reverting society to a state reminiscent of the Tower of Babel. What distinguishes legal immigrants like myself from illegal immigrants? Can compassion justify turning a blind eye to their inability to apply legally? Brother He pointed out the lengthy process—often spanning 7, 8, or even 10 years—required for legal naturalization as a U.S. citizen. Only through this extended journey can immigrants truly comprehend America and potentially embrace its faith, gaining a genuine understanding of the constitution and system. Unfortunately, many illegal immigrants engage in voting without a genuine understanding or identification with America, thus influencing its future. The media exploits public sympathy, manipulating American voters to support politicians who normalize illegal activities and treat invasion as inevitable. This fundamentally damages America, undermines its constitutional foundations, and ultimately leads it towards destruction. The entire educational and propaganda system indoctrinates the populace—a tactic commonly observed in communist countries. Our society commodifies people's empathy, crafting elaborate advertising campaigns and propaganda to indoctrinate this generation. In conclusion, Brother He posed a question: if my compassion led me to advocate for open borders, granting illegal immigrants unrestricted access to social welfare resources, would I extend that generosity to invite them into my home, sharing my bank account with them? I fear that my compassion may not withstand such a rigorous examination.

Like so many Christians, Jane Chin struggled with how to approach society's rapidly changing stance on LGBT issues. She wanted to know how best to love her neighbor while still remaining true to God's purpose and standards. So, she asked The Human Calling Author Dao Feng He for guidance: To help me think through this complex issue, I sought counsel from a venerable mentor in my life, Brother He. In our discussion, I asked why many within the Christian community find it challenging to embrace gender transition as a legitimate response to either mental or physical needs, akin to psychological treatments, surgeries, or organ replacements. Brother He prompted me to revisit the timeless phrase from the Declaration of Independence, "all men are created equal," underscoring the foundational tenet that without acknowledging one's creation, endowed rights remain an elusive concept. He questioned the alignment of gender transition with the Creator's intent and cautioned against undue influence from parents or school counselors on children, characterizing such actions as manipulative and, in certain instances, criminal. Thinking about the intense challenges of individuals grappling with extreme gender dysphoria or same-sex attractions, Brother He referenced Matthew 19:12 – "He that is able to receive it, let him receive it." On the subject of same-sex marriage, he explained that Scripture has already laid out the intricate relationship between marriage and celibacy. In the broader context, authentic freedom, Brother He argued, emanates from the limited freedom bestowed by God. Equality, a concept codified by laws, represents merely the tip of the iceberg, with the denial of God and the unchecked expansion of perceived limitless freedoms encroaching upon the liberties of others. This encroachment manifests in societal influences in educational institutions and public opinions, such as the controversy surrounding transgender athletes participating in women's sports. As our conversation concluded, Brother He recommended two books on the subject – "Mao's America" and "The Democrat Party Hates America." Drawing parallels between the historical Chinese Cultural Revolution and contemporary educational trends, he cautioned about the potentially destructive impact of various political movements on the fabric of the nation, with the elevation of LGBTQ+ education as a prime example. Departing with a profound sense of gratitude, I thanked God for the wisdom imparted by Mr. He, my mentor, shedding light on the intricate interplay between my faith and societal dilemmas. Most compelling was the realization that the issues surrounding same-sex and transgender discourse transcend conventional societal concerns, carrying profound political implications.

Since creation, men have grappled with how to order their lives and societies. Philosophers have developed a wide range of answers, and human history tells the story of the consequences. Will we learn the lessons of the past? Or will we blindly repeat the same mistakes? In the East, Chinese society was formed on large, fertile river plains that allowed individual family farms to become the core units of production. However, severe flooding made these family units highly dependent on government for infrastructure to control the waters, giving rise to a highly organized government and rigid hierarchical system. This birthed philosophies like Confucianism and Legalism that emphasized obedience to rulers and strict social order. Philosophers were concerned with the material, prioritizing usefulness over truth and minimizing the value of the individual, a disposition that has ultimately led to today’s highly-centralized Chinese government. Meanwhile, in the West, Greece's spread-out Mediterranean city-states led to an emphasis on trade, division of labor, and a more equitable social structure. As trade flourished, so did the exchange of ideas. Philosophers sought to discover truth and understand beauty. These ideas found their completion in the ultimate truth of Christianity. As the gospel spread, the values of freedom and the dignity of the individual flourished. This led to limited government and generous private charity. But around the Enlightenment, as extreme thinkers like Nietzsche and Rousseau urged the West to overemphasize human rationality and abandon the faith, those values began to diminish. Today, the West is following closely down the path of the East. The worship of money and technology has led to a renewed dependence on government and centralized power. People no longer seek God’s truth but instead pursue pleasure and expediency. The West is now faced with a choice: To rediscover the faith. Or to fall further into the downward spiral of extreme pragmatism. God has a clear and specific calling for humanity. Will we answer? Learn more in Daofeng He's The Human Calling

An excerpt from Dao Feng He’s The Human Calling After the Maccabean Revolt in Judah, the Hasmonean dynasty founded by the Maccabees maintained independence for nearly a century. But before they could rebuild the Second Temple, Rome’s legions that had swept through European, African, and Asian kingdoms and made them its client states found their way into Asia Minor. In 64 BC, led by Pompey, they ended the Greek Seleucid dynasty, which had been entrenched in Damascus, Syria, for over 300 years. The Maccabees, however, blindly resisted Rome, resulting in Pompey’s leading the Roman legions south to the holy city of Jerusalem. Jerusalem was besieged for three months. Pompey finally attacked from the north on the Sabbath, slitting the throat of the high priest defending the city, massacring over 12,000 people, and ending the reign of the Maccabean king. After appointing his minister Antipater as the new king and Hyrcanus as the high priest, Pompey, driven by curiosity, strode into the Holy of Holies in the Jewish temple that only high priests could enter once a year. After casting a contemptuous look at the sacred Ark of the Covenant and golden candlesticks, he left the treasures as they were and returned triumphantly to Rome. But his gross blasphemy planted seeds of hatred in the hearts of the Jewish people that would not be forgotten. In 55 BC, Crassus, one of Pompey’s key political allies in the triumvirate, his hands still bloody after defeating Spartacus and crucifying more than 6,000 captives in the forest, went to the holy city of Jerusalem. In order to fund war against the powerful Parthians to the northeast, Crassus stole countless temple treasures, including the solid gold beams in the Holy of Holies. His actions poured salt on the wound that Pompey had made, increasing the Jewish people’s hatred of the Romans for their violence, greed, and blasphemy. In less than a year, the proud Crassus was trapped and killed by the Parthians—in a sense, karmic retribution was in play. Meanwhile, King Antipater of Judea, as Judah had become known to the Romans, led 3,000 soldiers to rescue Julius Caesar in Egypt and so gained his trust and support. This enabled Antipater to further consolidate his power over Judea. His younger son Herod came onto the political scene at the age of 15 but provoked outrage because of his cruel slaughter of the Jews. The Maccabean prince Antigonus took the opportunity to lead the Jews in an uprising and returned to Jerusalem, the capital of Judea, with the support of the Parthians. King Herod’s brother was killed, while he himself fled Jerusalem. Herod knew how to take advantage of the Roman Empire’s violent nature to protect himself. He raised another army to aid Mark Antony, who was fighting against the Parthians, and was able to rescue him from an enemy ambush. In 38 BC, Antony repaid Herod for his aid by sending 36,000 infantry and cavalry south to help him retake Jerusalem from the Maccabean prince. After a two-week stalemate, the Romans broke into the holy city, savagely looted the sacred temple, and slaughtered the people. The Maccabean prince was beheaded by Mark Antony, and Herod again was crowned king. Of the 71 members of the Jewish assembly, known as the Sanhedrin, 45 were purged by King Herod. A new reign of terror had begun in Judea. King Herod was Phoenician by bloodline, Greek by culture, Jewish by religion, and a Roman citizen by status. As a result, he was one part international visionary, one part violent and cruel Roman ruler, and one part eloquent Greek speaker. After the defeat of his good friend Antony by Octavian, later known as Augustus, Herod not only stayed out of the fray, but also quickly gained the favor and support of Augustus. He sent his two sons born to the Maccabean princess Mariamne to Rome to be instructed by Augustus himself. Augustus also helped King Herod expand his power over a larger area to include Israel, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon, thus extending Israel’s territory to a point rivaling that of King David’s time. King Herod’s most brilliant achievement was the demolition of the old temple and the reconstruction of the Second Temple. He had it redesigned and refurbished in a way that married the style of Solomon’s Temple with Greek and Roman architectural and artistic elements. The temple stood on an elevated platform behind three gates, with the first gate located at the level of the 50th stair, and the second and third higher up. It was surrounded on all sides by colonnades that ended in the Royal Stoa, a massive basilica that overlooked the holy city, the Temple Mount, and the Mount of Olives. The temple, contrasting finely with an elevated piazza twice the size of Piazza della Rotonda in Rome, shimmered in the sunrise and sunset along with Antonia Fortress and the Mount of Olives. It was a consummate masterpiece that perfectly combined grand architectural design and the worship of Jehovah. It was regarded as a manmade wonder of the world at the time, attracting millions of pilgrims from all over the world each year. Generally about 70,000 inhabitants lived in the capital of the Herodian kingdom centered around the temple. King Herod married the Maccabean princess Mariamne in an attempt to gain Jewish favor. Mariamne, however, was still deeply obsessed with the fallen Maccabean dynasty and was intent on plotting rebellions at court. The royal couple’s love-hate relationship, mingled with political benefits and conflicts, culminated in Mariamne’s being sentenced to death by Herod. He then preserved her body in honey so that he could still see her. The two princes Mariamne bore him returned to Jerusalem after spending many years in Rome receiving education and even instruction from Emperor Augustus himself. Knowing that they believed him to have murdered their mother and desired revenge, Herod had no choice but to disinherit his sons and have them executed as well. The other 12 children King Herod had with other wives also joined the political struggles to try to usurp the throne. All these toxic rivalries and bloody assassinations completely wiped out the ties of kinship. King Herod changed his heirs and will several times until April 3, 4 AD, when he died of a putrefying illness after ruling for 37 years. Each elimination of an heir resulting from the political battles inside the royal Herodian family left countless people implicated and killed, including military personnel, priests, and even the poor. The kingdom of Judea was overwhelmed by violence and bloodshed. In addition to the burden of heavy taxes from both Rome and the ruling Herodian family to build the temple, King Herod’s palace, and the Masada palace-fortress, this made the lives of the lower classes unbearably miserable. Furthermore, Herod himself hailed from a Gentile family. His irreverent, greedy, corrupt, and cruel personality was a continual offense to Jewish faith and morality. At that time, the Pharisaic priests who controlled the Sanhedrin followed the lifestyles of the Roman aristocrats, living in luxurious Greek villas in the suburbs and indulging themselves in material desires. They worshipped many gods, and abandoned their faith in the Jehovah, marking a radical departure from over 1,600 years of the Jewish faith. At the time, doomsday pessimism was prevalent among three groups: the Sadducees, who held fast to the provisions of the Old Testament, the Pharisees, who explained and applied the Old Testament and the Prophets more flexibly to achieve their earthly goals, and the Essenes, who adhered closely to the Scriptures and lived a strictly ascetic life. This pessimism provided fertile ground for the Jewish hope of the Messiah. Their apocalyptic outlook and Messianic expectation was first formed in the great prophet Isaiah’s foretelling of his arrival, penned in 700 BC. He prophesied that God would send the Messiah to the human world in 700 years to carry out his rescue plan for humanity. The Essenes believed that Isaiah’s prophecy was coming true in their time. They were convinced that the end of the world was approaching, and that Jehovah had sent the Messiah to the human world to save Israel, bringing the Jews new blessings. This messianic hope was a source of spiritual strength that helped the Jews survive unprecedented worldly suffering in this extremely violent, bloody, corrupt, and degenerate society. While their eschatological hope and the expectation of the Messiah helped the Jews heal from their earthly suffering and trauma, it caused panic and unease among the rulers of Rome and the priests of Judea. Around 1 AD, there were rumors in Jerusalem that the Messiah sent by God had already been born in the Kingdom of Judea. King Herod, even in the throes of the end of his reign, sent troops to search door to door and have all newborn babies killed. After King Herod died, Emperor Augustus, who was tired of hearing reports about the cruel court fights of the Herodian family over succession, did away with the Kingdom of Judea and re-established the province of Syria. Judea was partitioned into tetrarchies among several of Herod’s children. Jerusalem was downgraded and placed under the rule of Herod Archelaus, while Northern Galilee was given to Herod Antipas. Judea became a land with more hierarchies, more complicated administration, and more intense social contradictions than ever before. Apocalyptic and messianic expectations became even more popular. As a result, rebellions constantly arose, led by those who pretended to be the Messiah but were in fact false prophets. But they were all suppressed by the Roman rulers and the Herodian family. Thousands of people were crucified. Both the rulers and the ruled lived in constant fear. Against this great historical backdrop, Jesus was born in Bethlehem to the carpenter Joseph and his wife, Mary. Read more in The Human Calling

An excerpt from Dao Feng He’s The Human Calling In comparing Chinese and Greek philosophy during humanity’s first great philosophical awakening, it’s not hard to see their similarities and differences. The two groups of philosophers, who never encountered each other, concerned themselves with four areas of inquiry, including how they operate and why: first, the nature of the relationship between humans and nature; second, the nature of relationships between humans and society; third, the analogous relationships between humans and society and between humans and nature, which are also homologous in their temporal and spatial dimensions; fourth, how methodologies of philosophical thinking and discussion can standardize, promote, and improve human thinking and imagination. These four areas of inquiry offer answers to questions of human calling . That is, how a person should recognize the world in which they live and the relationship between them and the universe, the relationship between people and things, and especially the relationships between people. How and why should people think and act in the world? How and why should they follow some guidelines and reject others? How and why should they face their own existence and death, and how and why they should think about and discuss these major issues in life? The reason philosophers from both cultures paid attention to and discussed these interrelated issues is because they’re the most fundamental problems human beings have faced since the start of agricultural civilization. The first problem they both tackled was how to stop or slow down the internal and external violence that arises in human life. This meant asking how to order community and public life to encourage better communities. Both Ancient Greece and China created organizations representing the interests of society: democratic city states and dynastic feudal states, respectively. Both types of states related in a certain way to private households and allowed for relatively simple tax collection for the public interest. But the two were very different. Ancient Greece was a civilization of city states in the Mediterranean islands. The combination of land and sea, as well as the openness and diversity of their trade patterns with other surrounding community states, gave them a more pronounced commercial DNA and a more obviously contractual basis for dealing with private and public issues. China, on the other hand, formed an agricultural society around the Yangtze and Yellow River basins and was therefore a relatively closed community. This resulted in a more obvious agricultural DNA when dealing with private and public issues and a more obvious tendency toward conquest and surrender. This could explain their differences in philosophical thinking. The second problem addressed was how individuals can anticipate their futures while unable to change the public order of community they live in. How could they both conform their life to that public order while also feeling joy, happiness, and meaning in that context? This question involved individual recognition of human calling but also certainly touched on a larger societal issue. Ancient Greece and China also differed in their philosophical inquiries. First, ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosophers nearly all emphasized the relationship between humans and nature. They sought to divine the nature and form of the world’s composition and existence. The public relationships between people and others may be influenced by the relationship between humans and nature. Among Chinese philosophers, only Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Mozi discussed this problem. Laozi and Zhuangzi’s discussion of the source of all things, dao , was not about deciphering the material structure and function of the natural world or the structure and function of the dao behind the phenomenal world. Rather, it was about affirming the supreme status of dao and guiding people to understand how they should act in this violent, ever-changing world. Only Mozi discussed natural philosophy like the ancient Greeks. Sadly, his ideas were never taken up by later thinkers. Second, the relationship between humans and society was raised and addressed to various degrees by most philosophers. Apart from Mozi and the Daoists Laozi and Zhuangzi, no one discussed whether human calling had any necessary or inevitable connection with existence beyond the material world. Confucians and Legalists were more concerned with the material. They were not interested in the abstract world beyond sensation. Confucianism was more concerned with common norms of behavior that people must adhere to when relating to others in public—its philosophical equivalent is the ethics of human duty . And these conventions and behavioral norms came from looking back to the previous dynasty in a way a baby always look to their mother, thinking she holds all the solutions to current and future problems. Ancient Greek philosophers, meanwhile, always turned their gaze to the gods. They thought universal, absolute truths were not found in the world of appearances but rather in the abstract world of the gods. This world existed prior to and would exist after life and the cessation of sensation, so truth and power can only be sought from God. Legalist practical philosophy, on the other hand, slipped into the practical politics of the public interest, emphasizing the power of harsh punishments to maintain order. It could be said that it bypassed human calling while going straight to human requirement , exchanging one form of violence for another, for the government was itself a violent mechanism with the intention of stopping violence. Only Daoist and Mohist thought discussed the metaphysical issue of human calling on the same level as ancient Greeks. They not only tried to answer why mankind needs a public order to coexist peacefully with others, but they also pointed out the path to realizing such an order and further uncovered the deep divine reasons in the invisible world for why mankind should think and act in this way. Third, regarding the homologous nature of the relationship between humans and society and humans and nature, ancient Greek philosophers expressed relatively obvious dualistic and humanistic polytheistic tendencies. A majority of philosophers believed that behind the material world there is a deeper, rational world. Nevertheless, the core elements that make up this deeper, non-phenomenal world differed. In the Milesian school, they were water, fire, air, or nothingness; in the Pythagorean school they were numbers, spirit, and soul; in the Elia school they were Mind and Eros, while water, fire, air, earth, and atoms were only materials used by them to form all things. Among the Socratics they were universal reason and highest existence; in Platonic thought they were sacred perfection and the eternal creator; in Aristotelian, the wise soul and eternal, unlimited, inevitable universal law of the gods. For the practical Cynics, it was the inner soul’s god-facing, wise virtue; for Epicurean hedonism, it was the godly and ordinary atoms composed of tiny atoms; the pre-existing concepts and philosophical reason of the Stoics with their ragged clothes and noble hearts; the sacred one and heart of the Neoplatonists school; the supreme light of God and intermediate soul of the Gnostics; and so on. But regardless of the differences between them, they all had a dualistic view of existence. They all agreed that beyond the physical world of sensory perception there was another world that could only be sensed through reason. Even the atomic theory of the Elia school, which many misread as monistic, was at its heart dualistic, since they believed the atoms that make up the material world are made up of Eros and Mind from another world. In fact, in this dualistic view, the first element is visible, individual, formal, and fluid. It wants to embody human ability and therefore participate in self-centered competition and struggle. Meanwhile the second element is spiritual and represents the “public spirit.” It is invisible and constant, a general law. Its core is love, compassion, goodness, and beauty. It wants to embody human calling through restraining selfishness, and transcend the first, physical element. It is the common origin of people and things in the physical world. It exists before us and does not disappear when we die. So human souls remain after they die, and join the higher existence of the spiritual world, whether it is “Mind,” “Eros,” “oneness,” or “eternal creator.” This dualistic worldview is the philosophical foundation of Western natural law. Whether it’s relationships between people or relationships between all things, all are governed by a homologous law. The search for how and why this homologous law was created eventually led the West to personal faith in God, which laid a solid cornerstone for philosophy. It could even be said that if it weren’t for the early exploration of the ancient Greeks, the philosophical foundation of the Christian faith would not exist and would never have been imagined. As far as dualistic thinking goes, the philosophers of China’s first axial age can be divided into two groups. The first is the Daoists and Mohists. On the surface they could be considered dualistic thinkers because the dao is different from the material world. To say that “ Dao creates all things” seems to imply that dao exists in a transcendent world while “all things” refers to the physical world. This means that Dao is the source of the physical world. But due to the inherent ambiguity in the ancient Chinese, the saying “Man rules Earth, Earth rules Heaven, Heaven rules Dao” could seem to imply that dao is a separate element from material things and the ultimate source of all things. Yet when you go on to read “ dao rules Nature,” following Laozi’s logic leads to the collapse of the dualistic worldview, since it seems to express a hierarchy of worlds rather than a dualistic worldview. Humanity follows the laws of the earth, the earth follows the laws of the sky, the sky follows the laws of the dao , and the dao follows the laws of nature. But isn’t nature all things? The world of dao follows the law of nature, but don’t all natural things partake in the birth and death of the physical? How can the eternal dao follow the law of living and dying things? How can dao still be the “source” as the creation of all things? Mozi, on the other hand, didn’t refer to the abstract dao but rather to Heaven’s will. He believed that spirits aid Heaven by meting out rewards and punishments that maintain mutual love and non-violence in the physical world, thus holding a relatively dualistic worldview. But he didn’t question or dig further into the common essence behind the relationships between humans and nature or between humans and society. His Heaven’s will idea loses its moral and sacred authority. As more spirits aid Heaven, these spirits lose their moral authority and slip into witchcraft and mysticism. Yet, Mozi explored the relationships between time and space in the physical world, movement and resistance in time and space as well as other mathematical relationships like points, lines, surfaces, and leverage. He is the only Chinese philosopher to have studied the relationship between the structure and function of all things in nature. The most fundamental difference between the worldview of the Chinese dualists, the Daoist and Mohists, and the dualistic worldview of ancient Greek philosophy is that the dualistic worldview of Chinese Daoism and Mohism is naturalistic in nature; in other words, the law behind all things in nature (either the dao or the will of Heaven) determines the law of human relationships. Thus, in Chinese philosophy, the hierarchy that places Heaven above earth is echoed in the difference between human beings of high and low status. This thinking could not possibly give rise to the idea that all humans are free and equal. This essential difference has profoundly influenced the diverging development of civilization in East and West. As for the Chinese monists, at least Confucians and Legalists lived and interacted more directly with the visible, physical world. They believed that Confucian ritual and laws, constraints, and orders, were just methods of organizing the monistic world. And this physical order’s hierarchy was based on their individual opinions. But they were not concerned with and did not recognize another world beyond what they could see and feel. They were not concerned with a meaning or power beyond the individual. They were even less concerned with agonizing over the meaning of life before life or life after death. They were only concerned with the public order of human life in the present. From the perspective of time, an individual life had no origin or future, unless it was placed in the physical context of blood flowing through the body. As a result, atheism and the veneration of ancestors were the logical cultural legacy of this monistic worldview only concerned with the material world. Fourth, the issue of philosophical methodology was raised in China, but only by Mozi. His analogical reasoning was truly unique. But in terms of the rigor and systematic nature of formal logic, it didn’t come close to Aristotle, which is why Aristotelian logic still guides both the social and natural sciences today. Modern natural sciences originated from natural philosophy, and social sciences originated from humanistic philosophy. Aristotle’s formal logic contained concept definition, scientific classification, empirical induction, and deductive reasoning, and was systematic and rigorous. However, in terms of methods of dialectical logic, the Daoist doctrine founded by Laozi was equivalent to contemporaneous ancient Greek’s Pythagorean school, not only it its discussion of how all things contain the unity of opposites, but also in its in-depth explanation that what we perceive as change in the material world is caused by opposing forces and the dao beneath all things. A wise ruler is called to recognize and follow the dao through “non-action,” which prevents him from acting recklessly. Individuals are called to recognize and follow this dao by seeking what makes them aware, at ease, and at peace. This control and grasp of the dialectical philosophical method is similar to the logic of “have, lack, change” Hegel articulated in the 19th century, 2,300 years later. This mastery and grasp of philosophical dialectics is as mysterious and profound as the Rig Veda and Upanishads of India, and has long influenced Chinese and Eastern thinking and cultural paradigms. Ancient Greek philosophy greatly furthered mankind’s ability to think and reason about human calling . It expanded the spiritual world imagined by humans in its dualistic thinking. This spiritual world was actually a space mankind created for the public spirit. It reached many pinnacles in humanity’s history of philosophy that have yet to be surpassed. But it still did not succeed in saving the ancient Greeks from their civilization’s tragedy. When Aristotle’s student Alexander the Great used his cavalry, swords, and fiery enthusiasm and natural talent for war, the brilliant culture of Ancient Greece spread far and wide. It swept through India, Central Asia, Asia Minor, Egypt, and North Africa. After victory Alexander the Great was like a Greek god of war in the realms of mortals. But after he had conquered the known world, his heart still longed for something more. There was no spirituality in the deep rationalism of his teacher Aristotle. So he went down along the Nile, through the jungles of Ethiopia and Uganda to mysterious Lake Victoria and asked a priest to tell him his fate and the secret of immortality. His fate was an early death, but his name will be known forever. The young and vigorous 33-year-old Alexander the Great was like the gods Uranus, Chronos, Zeus, and Dionysus in the Greek tragedies: able to defeat all their peers, but unable to defeat their own destiny. He abandoned his human empire in the mortal realm and left it behind. Subsequently the ancient Greek empire was quickly divided due to an absence of rightful heirs and declined gradually, making room for the Roman Empire and its philosophy of human calling , which was completely incomparable to that of the Greeks. Where, then, can we go to once again find the confidence, passion and diversity of answers that the ancient Greek philosophers brought to the question of human calling ? How can we avoid the fate of the gods and men of ancient Greek tragedy? What use are the ancient Greek philosophers to mankind’s quest for human calling ? These questions are left to the generations that came after. Chinese philosophers during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, on the other hand, reached a different pinnacle in Eastern philosophical speculation. Their thought didn’t develop in the context of centuries of peace and democracy like that of the ancient Greek commercial city-state civilization. Rather it developed in an agricultural civilization experiencing hundreds of years of turbulence. As a result, it was not as quiet and calm as ancient Greek philosophy. This prevented Chinese philosophers from considering the purely spiritual side of the dualistic world. Instead, they spent more energy in reconstructing the public order of the physical world. Even Daoists and Mohists who deeply considered the dualistic worldview were inevitably dragged into the politicking involved in reconstructing public order in the physical world. As a result, discussions of human calling turned to more real-world discussions of how humans should behave, human duty , in Confucianism or how to impose the law, human requirement, in Legalism. To Confucians, without training in the thousands of conventions for thought and behavior encoded in the Zhou rites, which constitute human duty , a peaceful, ordered society could not be rebuilt. People could not become benevolent without understanding the spirit of ritual and music. Legalists, on the other hand, thought Confucian rites were useless, instead prescribing laws, constraints, and orders to impose the ruler’s authority and regulate people’s behaviors through human requirement . If violators faced harsh punishment, others would be deterred, and a non-violent order would naturally be restored. Legalist methods were used to build the insignificant State of Qin into a great empire that conquered and ruled all the other states. Confucian methods were used by the Han, which succeeded the Qin after its collapse. A combination of Confucianism and Legalism replaced the way of kings of the Zhou Dynasty, to pave the way for the hegemony of the Han Dynasty. Daoists and Mohists, meanwhile, were continually plagiarized by the Confucian-Legalist literati after the Song Dynasty, becoming phantom echoes in the culture. In this sense, the Chinese philosophy of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods was more practical than that of the ancient Greeks. But over time it lost focus on the issue of human calling , whether this was the question of human free will, the hope for goodness and beauty, or questions of human equality. It ignored fundamental questions of human life, such as spiritual freedom and equality, instead concentrating on a combination of human duty and human requirement in the material world. The spiritual world, which humans could only encounter at divinely appointed times, was missing altogether. But where is the individual, spiritual free will outside of public order? Is there another invisible world that exists beyond and prior to the physical one we perceive? How does a mortal man with no consciousness before birth and after death face his inevitable mortality? Is the overall public order of society really all that matters? Does a public order that demands an eye for an eye and castrates the free will of the individual harbor an even more horrific political violence? These questions were also left for subsequent generations. Read more in The Human Calling

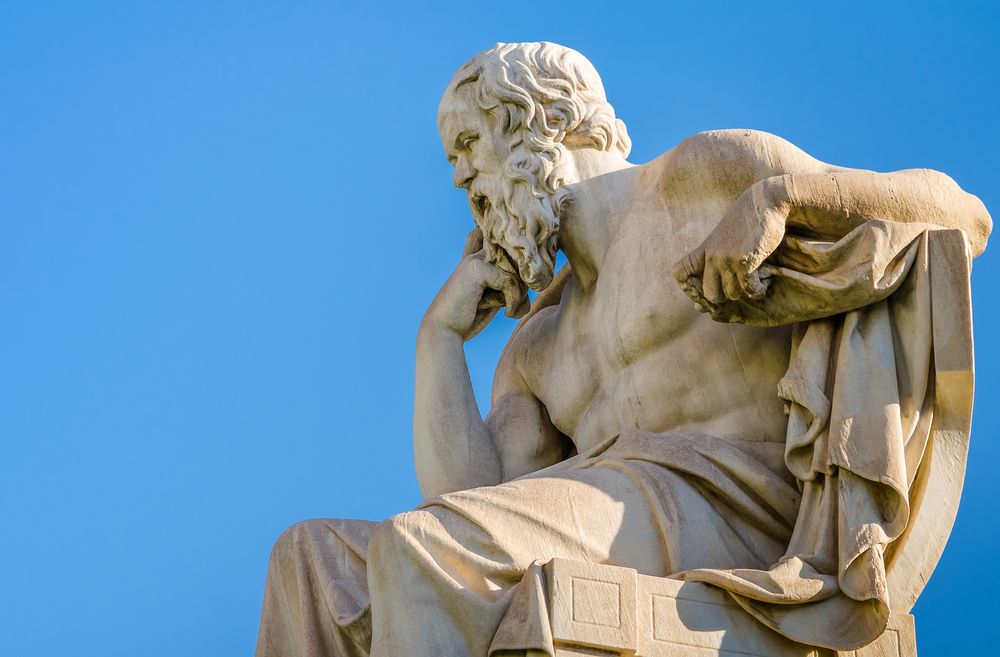

Read more in The Human Calling Aristotle began as Plato’s student at age 18, and he followed him for nearly two decades until Plato’s death. Plato constrained rather than pushed him. Aristotle spent eight years tutoring Alexander the Great, who later led Macedonia to conquer Greece. He had a profound impact on Alexander’s brief yet glorious life and founded the Lyceum and its library with his patronage. Aristotle comprehensively, systematically, and completely integrated the different schools of Greek philosophy and pushed it to its peak. Aristotle believed that thinking is driven by human curiosity and that freedom is the unrestricted ability to do such thinking and so gain the power of true knowledge. He inherited Plato’s idea that there is a universal hidden behind all particulars. Yet, while Plato held that the universal exists independent of the particulars, Aristotle argued that the universal can only exist in individual things and that the two are in mutual opposition and mutual dependence. Regarding the world that we can see, individual objects comprise the most real and visible existence. That’s because each object is the product of the combination of what he called matter and form. Matter is an object’s potential, or the cause of an object’s purpose; form is the shape of the thing or the cause of its form; the reality of things is made up of the combination of the two—their function or the cause of their effectiveness. Everything has a “material cause,” a “formal cause,” and an “efficient cause.” Aristotle believed that living beings are different from other objects because they have life—that is, the nutrition-fueled process of birth, change, and death. The soul of a living person is his material cause, the body is his form or formal cause, and his existence is his realization or efficient cause. The soul’s function is contemplation, and its form is different from the body’s form. The body’s form is primarily related to the four elements of earth, air, water, and fire, while the soul is most related to a fifth element, the divine Aether. Humans do not become skillful animals because they have hands. Rather it is the soul’s wisdom that allows them to manipulate countless tools and objects skillfully with their hands. The soul, however, is not something that only humans possess. Plants have a vegetative soul, since they ingest other things while maintaining their distinctness from these things, allowing for infinite self-replication. Animals have a sensory soul, since they sense other things while keeping themselves independent from those things, and they also infinitely self-replicate. Humans have a rational soul, since they perceive other things through thinking while existing independently of them, and they seek reason and holiness.50 The human soul, then, represents a higher existence. Aristotle further developed these concepts of the soul. He argued that there’s a difference between the human soul and wisdom, because there are various levels of universals among individual beings, like “species,” “genus,” and “class.” For instance, the lowest universal, species, is most closely related to the individual being, and vice versa. That means that higher-order existence contains the lower. The realization of lower-order existence creates the potential for the realization of the higher, and all lower-order existence serves as the preparation for the higher. For example, the human soul both incorporates the reproductive power of the vegetative soul through ingestion, and the sensory power of the animal soul in its ability to stay separate from other beings. This is something that humans, animals, and plants have in common. What differentiates human individuals from each other is the rational mind, and the universal behind it is the pursuit of virtue and wisdom. The supreme universal is God. God is the eternal, inevitable, and absolute realization. “Time” and “essence,” embodied in God, both exist before the individual experience of humans. Thinking that reasons from universals to particulars Aristotle called “deduction” or “reasoning”—for instance, reasoning from the first universal, God, all the way down to specific objects. He termed thinking that begins with individual objects and argues toward the universals of species, genus, class, and finally God, as “induction.” For Aristotle, mankind’s purpose is to contemplate and reflect on the phenomenal world through induction, ultimately realizing that God is eternally perfect and that his soul is the “sacred soul.” This is the key to solving the problems of a lack of public spirit and code of conduct. If people can’t orient themselves toward God, they will deviate from law and justice and fall among the most wretched animals, full of greed, evil, and cruelty. God’s justice, then, is the yardstick of human politics and the basis for the orderly operation of the human political community. Aristotle spent a great deal of energy discussing his method of pursuing reason, wisdom, and sacredness—which he called Logos . He formed a complete academic system of logic based on deductive and inductive reasoning, laying an unshakable methodological foundation for logical discussion and study of both humanistic philosophy and natural philosophy over the following 2,000-plus years. To this very day, our social and natural sciences can’t do without Aristotle. His philosophical methodology is guided by three aspects: classification and definition, dialectical logic, and formal logic. His methods for accurate classification and definition open the door for scientific discoveries as well as technological innovations. He was the first to use dialectical logic to analyze the unification of the opposites of matter and form, bringing to light the law of conflict and unification in all things and providing a way to discover the changes caused by these conflicts. This method has had far-reaching and long-lasting significance. Lastly, he based his formal logic on what he called a syllogism, a three-stage method to reach conclusions with a major premise and minor premise. This method is universally applicable for rigorous deductive and inductive reasoning. It has guided the methodology of thought, exploration, and argument over thousands of years in human history. Built on these foundations, the natural and humanistic philosophies that began in ancient Greece eventually became today’s social and natural sciences. Read more in The Human Calling

Read more in The Human Calling Socrates prevented the moral decline of the Greek city-states. He started a boom of ancient Greek humanistic philosophy. The small and large Socratic schools were born. But the most important thing he gave the world was his outstanding disciple Plato. At age 20, Plato was obsessed with poetry. Socrates’ philosophical arguments so inspired and shocked him that he burned his beloved poetry and followed Socrates. This lasted for ten years until Socrates was sentenced in 399 BC, and Plato and other followers went into exile to Megara. Plato gained experience through hardship. Dionysius I of Syracuse almost sold him into slavery, but a friend bought his freedom, and he went back to Athens. There, he founded the Academy, based on his philosophy. He spent the rest of his life in discussion with his followers, living until the age of 81. He left a great number of dialogical works in which Socrates is the main participant. The breadth of the contents and depth of the expositions in his works form an unprecedented ancient philosophical encyclopedia. Anyone researching any philosophical question ever since must return to Plato’s texts. Plato believed that the Sophists exaggerated the usefulness of individual sensory perceptions of the world. He compared individuals in the material world to a group of cave dwellers chained to the wall for all of their lives whose only view of the outside world is through the shadows projected by the fire onto the cave wall. Their senses mistake these shadows for the world itself. If one of the cave dwellers were to break free and see the outside world, he wouldn’t believe his eyes and would think it was a mirage. If someone seeing the outside world came back and told the other captives what he saw, they would laugh or even kill him, because those who have been accustomed to the world of darkness and shadows are afraid of the light and afraid of the truth. He concluded, “the conceptual world exists prior to and is a higher existence than the world of sensation.” People gain knowledge of these concepts through sensations. On some level, it’s almost as if people must recall or be awakened to their existence. The conceptual world not only exists a priori but is also universal and ordered. Sensation is not enough to understand the world—humans need to merge it with higher concepts in order to consider, understand, and name it. But where does this conceptual world come from? Plato’s Timaeus affirms that the eternal creator of the conceptual world is God. As God is perfectly good and absolutely free, he created the world based on his desires and ideas, turning the world from formlessness to form, chaos to order, emptiness to existence. Creation is the unity of God’s conceptual thought and action. The human body is just a tool for sensations. The opinions people form through sensations disappear with the death of a human’s body, but not the concepts of God, like justice, beauty, goodness, and eternal existence. When people embrace these ideas, they participate in the mind of God and gain pleasure from the perfect good. God is this Good, the cause of good, the realization of good, and the perfection of good. In the Republic, Plato goes on to argue that the human body as a tool is only able to produce illusions. The soul, however, has three abilities: appetite, passion, and reason. It’s only through the soul’s ability to reason that humans can attain true knowledge. The goal of life is what Plato calls the Good. In order to reach the Good, people need to engage the three powers of reason to make the most of the soul’s abilities: temperance, courage, and wisdom. In order to promote this reason in society, the city-state must promote education so that the public good is learned and known. It must make laws to guide the public good, and so help individuals to achieve the Good. In such a city-state, craftsmen represent temperance, guardians represent courage, and rulers represent wisdom. Education must cultivate temperance through music, courage through athletics, and wisdom through philosophy. Education must also encourage the pursuit of beauty. Plato’s Symposium and Phaedrus deeply explore the logic of love and beauty. He held that behind erotic love is a deep drive for immortality. It’s natural, then, for humans to long for the beauty they see in another body and to join with it to create a child and so perpetuate their life. Fame is another, more effective means of overcoming mortality, and when people realize this, their efforts are even more extraordinary. For philosophers, fame, or reputation, was considered a more beautiful way to pursue immortality, because they tend to find knowledge more beautiful than the body, and the soul even more so. The conception of the soul is more likely to evoke a sense of eternality. That’s why philosophers are more enchanted by the soul’s beauty than by the body’s beauty. With this in mind, Plato encouraged people to recognize their own erotic desire and lift it to an increasingly higher plane—from the pursuit of a beautiful body to the pursuit of a beautiful lifestyle, then to the pursuit of beautiful knowledge, and finally to the pursuit of beauty itself, the divine, pure, ultimate beauty. For him, “only the most beautiful life is worth living.” In the Phaedrus, Plato discussed the premise that the soul exists before the body. Logically speaking, the soul dies after the body, but the soul also exists before the body. For Plato, the “pre-existence of the soul” is proven by the fact that education can awaken people’s “memories” of knowledge, but primates aren’t capable of such awakening. The soul can unite with reason and so participate in God’s thoughts. In this way, humans can reach eternal truth, which allows them to acquire virtue and wisdom that can guide individual behavior. Plato also held that after death, there is an afterlife. Souls must accept God’s judgment, which doles out rewards and punishments according to the good or evil of their actions. It’s the responsibility, then, of all human beings, rich or poor, to share in the public spirit, take public responsibility, do good rather than evil, and unite their souls with divine reason.48 Plato introduced the concept of the soul and God as invisible realities, as opposed to the visible, physical human body. In doing so, he revealed the truth behind the phenomenal world, namely, mankind’s latent longing to unite his soul with God. He provided some of the earliest and most philosophical insights into human calling , all while facing violent challenges. Future generations have continually explored the profound meanings of Plato’s insights. Those who truly understood their profound philosophical significance came 500–800 years later: Christian theologians Paul, Clement, Origin, Tertullian, and Augustine. They were the first to fruitfully integrate Plato’s philosophy into Christian theology, which laid a deep theological foundation for its subsequent flourishing. Read more in The Human Calling

An excerpt from Dao Feng He’s The Human Calling The Sophistic movement only valued physical individuals and discarded humanity’s public personality and spiritual rationality. It was popular, not only because it catered to the individualist trend needed for political democracy of that era, but also because it greatly satisfied society’s desire for public speeches that featured more shallow logic. But this market-based sophistic teaching severely damaged the tradition of philosophical contemplation in the pre-Socratic era, filling the whole society with superficial opinions based on personal feelings in oratory competitions—which were based on skill with words rather than logical guidelines. Of course, the feelings of individuals vary from time to time and from place to place, depending on their psychological differences. Over time, these feelings are subordinated to secular calculations of personal interest, especially in an environment like the ancient Greece of the sophists. When this happens, an individual’s public personality is lost. Public reason is lost. Public truth and public order are lost. Mankind becomes an animal possessing only individual personality. Among younger Greeks, the spiritual world had collapsed. Honor, devotion, and the spirit of obeying oaths and pursuing truth were all lost. Ancient Greek philosophy’s reflections on human calling faced unprecedented challenges. It was against this historical backdrop that the great Socrates burst onto the scene. Socrates’ thought acted as a watershed in Ancient Greek philosophy, which is why most present-day discussions of philosophy start with him. Pre-Socratic thinkers were mainly focused on natural philosophy: What is the origin of all things in the universe? What is the phenomenal world made of? Do the laws of the rational world and truths about a supreme being exist, and if so, how? What can humans learn from such inquiries and how should they affect their public personality and behavior? By contrast, post-Socratic philosophers tended to focus on humanistic philosophy (or to combine it with natural philosophy). They mostly discussed whether there is a higher existence, that is, a soul beyond a human’s physical body that lives on after their death: Should humans be dominated or stimulated by this higher existence? Is this supreme existence virtuous? How should humans deal with joy and happiness? How should their public personality be reflected in the community? And what logical methods should be used to discuss problems and pursue absolute truths? Socrates’ thought is what catalyzed this shift. The second reason history considers Socrates so pivotal is that he applied his unique way of thinking and questioning to interpret his deep considerations of humanistic philosophy, reflecting this in the way he personally acted and even in how he died. Socrates made his mark as the first great ancient Greek humanistic philosopher. Socrates started from the prevailing sophistic thinking of his era, but he didn’t begin elaborating his own views or universal truths right away. Instead, he traveled around asking the Sophists to debate with him. He brought his sacred virtues and skepticism of Sophistic thought to bear on his interlocutors, using constant questioning to corner them. He shocked and disturbed the Sophists, provoking them to reflect on universal, public issues that stand behind individual, physical lives. People became aware of how absurd the solely pragmatic and individualistic atomism that the Sophists preached truly was. Socratic thought, in contrast, held that behind each individual’s behavior and each workers’ technical experience, stand universal laws that are external to and above them, such as justice, beauty, and usefulness. These universal laws exist as ideas that precede human action. They guide it and reflect its deeper values. They serve as the reasons for humans to act in the first place and provide a standard of perfection to measure the results of those actions. The guidance of these pre-existing universal ideas and the reflection on behavior they provoke create a community that’s more orderly and more worth living in. People are not, as Sophists claimed, individualistic animals that act entirely based on their own feelings with no ability to pursue wisdom or truth and reflect on their behavior. On the contrary, Socrates’s question-based inductive reasoning proved that every ordinary person has wisdom and virtue and that this wisdom and virtue exist as the universal supreme being above individual feelings. They are the moral pillars that support the natural world and the rational world. So Socrates famously admonished individuals to “know thyself,” and to know the relationship between themselves and the supreme being, achieving their full potential through rationality and self-restraint. Socrates lived a simple, natural, and almost slovenly or unrestrained life, disregarding others’ praise or criticism. But underneath lay a deep public purpose and his commitment to the perfect virtue of human calling. He sought out debates and deep conversations with people, regardless of their status or wealth. Through systematic questioning, he awakened people to the importance of contemplation. He encouraged them to reflect on the variety, individuality, and non-universality of their personal feelings, so they could see the hidden virtues of justice, beauty, and usefulness behind them. Through promoting the profound significance of these virtues, which transcend the life or death of any individual, he dismantled the trap of the amoral, extreme individualism spread by the Sophists. His way of life gained him widespread approval and many followers. When Euthydemus, who thought of himself as knowing everything and embodying justice, experienced Socrates’ relentless questioning, he concluded, “The only way to be a worthy man is to talk to Socrates as much as possible.” With some, though, he was less popular. His unique style of questioning and irony embarrassed many self-righteous and high-ranking people, drawing the ire of interlocutors, the attacks of Sophists, and the sarcasm of other writers. Socrates, for his part, did not pay them any attention and kept living the way he wanted. Socrates demonstrated his philosophy and values throughout his life, and even through his death. He showed that he believed in the supreme, eternal, and universal existence beyond physical life. This existence is essentially made up of absolute truth, divine virtues, and the immortal soul, which are independent of individual feelings. Although his lifestyle from the outside seemed unrestrained, Socrates had a deep respect for moral law and social order. He despised behavior that ignored human calling in favor of personal interests. That doesn’t mean he didn’t value individual freedom. On the contrary, he truly appreciated creative artists and philosophers who transcended existing social codes, even if their creations caused shock among society and drew widespread criticism. These artists and philosophers were often judged and tortured for being mavericks in their times, but the next generation saw them as martyrs and heroes who voluntarily broke the laws in pursuit of the supreme being. For them, truly legitimate behavior, or human calling, means “voluntarily becoming a criminal," or more specifically, sacrificing oneself in pursuit of the supreme being. For them, the real sin was challenging existing laws just to make others suffer. Socrates also had unique views on death. Death, in his view, is the doom of the physical body rather than the complete demise of the human being. The deeper existence—the soul—doesn’t necessarily perish, so it’s not so terrible to die for the sake of human legitimacy or human calling. His own philosophical reflection and understanding of the truth informed the way he handled the ancient Greeks and led to what is known as the “Trial of Socrates.” He refused to be exiled and refused to appear in court for his crime of “corrupting the youth.” He even refused to settle with the court. Instead, they were forced to debate Socrates. His questions showed the flaws in their argument, but his arrogant attitude angered the jury of 300, and in the end, he was sentenced to death. Socrates seemed perfectly satisfied with the verdict. He chose to submit himself to the law of his city-state and not resist. He rejected any kind of compromise or appeal. Finally, he burned incense and bathed, talked and laughed with his followers. Then he drank a cup of hemlock with complete composure and bid goodbye to the material world, and its people—always scheming and plotting for their own interests. He devoted his life to showing how it was honorable to voluntarily become a criminal in pursuit of supreme truth. He also sacrificed himself for the beauty of the public order in the human community, with this final dispatch on human calling: “a life without thinking is not worth living.” Socrates became the second ancient Greek philosopher, after Anaxagoras, to be tried and the third ancient Greek philosopher, after Zeno and Empedocles, to die in pursuit of truth. His life and death mark a historical milestone in Greek humanistic philosophy’s reflection on human calling. Read more in The Human Calling